Financial intermediaries and banking institutions play a vital role in promoting economic prosperity, as they enable individuals and businesses to access the capital and financing they need to grow and succeed. However, in many emerging nations, banks can be vulnerable to regulatory and political interference, which can lead to distortions in the global economy. Access to capital and finance is crucial for the success of any business operation, and unequal access to these resources can hinder the growth of companies with limited credit opportunities. To address this issue, governments often implement policies that promote credit growth across all sections of society.

In India, the Reserve Bank of India defines any loan or advance for which the principal amount or interest payment has been past due for 90 days as a non-performing asset (NPA). NPAs are a significant prudential indicator of financial health, particularly in an economy where banks play a fundamental role in providing credit. Accumulated NPAs can have adverse effects on the efficiency of the banking system, hindering its smooth operation and posing a burden on financial stability. In addition to asset quality, NPAs also reflect credit risk management and operational effectiveness, affecting profitability, interest income, and solvency in India. Thus, minimizing NPAs in the financial system is crucial for promoting the stability and growth of the economy.

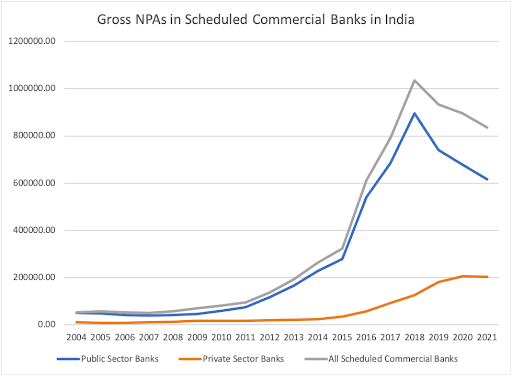

Evolution of NPAs in India

India witnessed tremendous economic growth between 2004 and 2009, leading to businesses aggressively borrowing money from banks. The infrastructure sectors like highways, power, aviation, and steel received most of the investment. However, banks' lax lending standards, without considering businesses' financial standing and credit ratings, resulted in an increase in NPAs in India. The suspension of mining projects and delay in obtaining environmental permits caused a significant mismatch between supply and demand and an increase in raw material prices. This particularly affected the steel, iron, and power sectors, making it difficult for businesses to repay bank loans, leading to a surge in NPAs in India.

The global financial crisis of 2008 exacerbated the situation, leading to severe financial stress for both the banking industry and businesses. Such a scenario is called the Twin Balance Sheet Problem. Political factors, including crony capitalism, have also contributed to India's high NPAs. Moreover, significant frauds in recent times have added to the rise in NPAs. Although the size of frauds is relatively minor in comparison to the entire amount of NPAs, these scams have been growing, and high-profile defaulters like Vijay Mallya and Nirav Modi have not yet been punished.

The following graphs give us an idea of how NPAs tend to accumulate over time in the Indian banking sector.

Figure 1

Gross NPAs in Scheduled Commercial Banks in India (in Rupees Crore)

Note. Author’s Construction. Source: Reserve Bank of India.

Figure 2

Gross NPAs in Public Sector Banks (in Rupees Crore)

Note. Author’s Construction. Source: Reserve Bank of India.

The RBI's Database of Indian Economy shows that public sector banks have more NPAs than private sector banks. Public sector banks are usually entrusted with improving social equity in India by priority funding rural development and providing programs for the underprivileged. In India, the RBI has mandated scheduled commercial banks to allocate a specific amount of their lending to a few distinct sectors that have historically had limited access to credit. This practice is known as priority sector lending (PSL), and it is a vital aspect of promoting economic development in the country.

However, Figure 2 shows that PSL has played a significant role in determining the level of NPAs in India. In fact, PSL NPAs account for approximately 50% of all NPAs. One concern is that the PSL NPA rules allow banks to have loose spending restrictions and may even enable them to exaggerate the value of the assets they hold on their books. This has led to some criticism of the PSL system, with some arguing that it needs to be reformed to prevent abuse and mismanagement. Despite these concerns, PSL remains an essential tool for promoting economic growth and providing critical support to underserved sectors in India.

Comparing India’s NPAs with the rest of world

In June 2017, India’s NPA ratio was the highest among the BRICS countries, standing at 9.9%, with a burden of over Rs 7.33 lakh crore. To address the issue, the government announced a plan to recapitalize public sector banks with Rs. 2.11 lakh crore and an additional Rs. 1.35 lakh crore via recapitalization bonds. And the situation has improved since then. India's gross NPA ratio dropped to a six-year low of 5.9% in March 2022.

While the NNPA ratio stood at 1.7% in the same period, it still indicates a high NPA ratio compared to other major economies in the world. Macro-stress tests for credit risk indicate that India’s scheduled commercial banks are well-capitalized, and all banks are expected to meet capital adequacy even in challenging stress scenarios. However, India's NPA ratios are still concerning, with the economy lagging behind most of its peers except Russia. Despite the challenges, policymakers remain committed to addressing the issue and implementing measures to ensure sustainable economic growth for the country.

Figure 3

Gross NPA Ratios for Major Economies in the World

Note. Author’s Construction. Source: CareEdge.

In China, financial institutions were tasked with funding State-Owned Enterprises to preserve employment, resulting in a high gross NPA ratio of 20%. To tackle the NPA problem, China adopted four main strategies, including bolstering banks, driving SOE reforms, permitting asset management firms, and debt-equity swaps. They also provided incentives like tax discounts, exemptions from administrative costs, and open evaluation standards. In contrast, India's NPAs primarily originate from private businesses and occasionally priority sectors with low returns on investment.

The Indian banking sector has very little exposure to public enterprises, and the NPA resolution procedures in India are significantly different from China's, making it challenging for capitalist economies to replicate Chinese banking reforms. China is reportedly testing asset-based securitization as a strategy to address their present NPA problem, with a focus on local investors. To tackle the issue of bad debts, Indian public sector banks must implement an effective technology-enabled information system that can segment data on new NPAs, write-offs, compromise settlements, recovery, and restructured accounts. This will help the banks to identify potential problem areas and take proactive measures to manage their NPAs effectively.

However, implementing a system alone will not solve the problem. Banks must also enhance their due diligence, credit appraisal, loan screening, and post-sanction credit monitoring systems. These measures will ensure that banks are better equipped to assess the creditworthiness of borrowers and reduce the likelihood of NPAs. In addition to regulatory measures, banks must also focus on improving their customer service and strengthening their recovery mechanisms. By providing timely assistance to borrowers and offering flexible repayment options, banks can reduce the risk of NPAs and preserve their asset quality level.

It is important for banks to address the issue of NPAs promptly and effectively as it can have far-reaching consequences for the banking sector and the economy as a whole. By implementing a holistic approach to managing NPAs, public sector banks in India can improve their financial health and contribute to the country's economic growth.

Twinkle Adhikari