In 2018, a Native American writer’s tweet went viral asking if women took any measures to avoid violence on a regular basis. Several women retweeted sharing their own instances of escaping violence or dealing with the fear and paranoia of potential violence in their lives. Though extensive research has been undertaken to account for the violence women face in their lives, have we really investigated the depth and impact of the fear of violence with which women deal? This article attempts to identify ‘fear of violence’ as a form of symbolic violence and traces its implications for the gendered use of space.

A Culture of Fear: Fear as Symbolic Violence

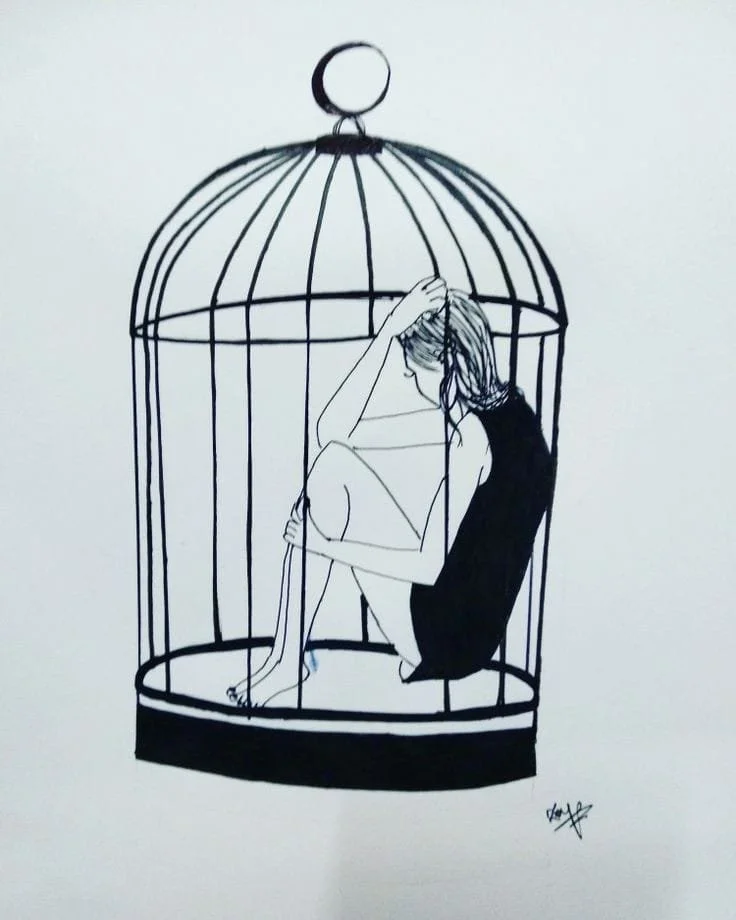

Several covert forms of oppression and violence often remain invisible and unrecognised. These forms are what Bourdieu coined as ‘symbolic violence,’ which is “a gentle violence imperceptible and invisible even to its victims exerted for the most part through the purely symbolic channels of communication and cognition (more precisely, misrecognition), recognition, or even feeling”. Symbolic violence does not work “directly on bodies but through them” and therefore “reproduces relations of domination.” One such form of symbolic violence that often remains unrecognized is the ‘Fear of violence.’

Although mostly understood in psychoanalytical contexts, fear becomes an important sociological field of study when we try to understand the social forces that influence fear. Studies indicate that women have higher levels of fear than men, particularly the fear of violence. Research explains this association by defining the role of media and other socialisation agents, which identify crime and victimisation in specific stereotypical ways. Not only are women socially identified as ‘weak’ or easy to victimise but they are deemed perpetually unsafe. These socialising agents induce a ‘gendered’ fear of violence in women that is used as a tool to control and manage their behaviours. Girls, for instance, are taught at a young age to restrict their bodies, physically and sexually, "for their own sake”. “Something bad is going to happen to them” becomes a common and trusted axiom that governs their lives and teaches them “their place,” i.e. who should or should not be protected or what type of behaviours can help avoid crime. Women, therefore, have to live in a “culture of fear” wherein fear is experienced over a sustained period of time and is normalised.

Fear, therefore, becomes a ‘symbol’ of violence and is used as leverage to keep women within restricted spaces and make social, economic, and cultural equality inaccessible.

Fear of Violence and Gendered Use of Space

Fear of violence among women can be easily traced through their use of ‘space’. The identification of public spaces with a lack of safety and fear is what Valentine (1989) identified as the “spatial expression of patriarchy.” Anxiety around public spaces like transport centres, clubs, or the city streets emanates from a common belief that violent predators are a feature of the public or ‘outside’ domain.

Therefore, the “Lakshman Rekha” becomes omnipresent, carving spatial and social boundaries for women everywhere. Self-regulation pushes women to make mental maps of the places they consider to be dangerous as opposed to those they find ‘safer.’ Spatial limitations translate into economic, occupational, and educational constraints as well with young girls finding lesser opportunities for growth. The induced fear of the ‘outside’ is also used to socialise girls into choosing ‘safer’ options. For example, Siddique (2020) in a study showed how media reports of sexual assaults caused a decrease in urban women’s likelihood of going outside their homes for work. Similarly, inaccessibility to ‘safe’ spaces not only exacerbates social vulnerability and creates increased dependence on family or male counterparts but also reinforces the fear of violence. Fear is used to push women into “patriarchal bargaining” wherein they negotiate their freedom and power for social access.

Fear of violence created by media and crime statistics promotes the spatial public/private binary. This not only identifies the home as a safer and nonviolent place but also helps justify keeping women within the “Lakshman Rekha”. As a result, violence occurring indoors goes unrecognised and unreported. A NIMHANS survey (2022) reported how women in Bengaluru feared violence by drunk family members or intimate partners. This indicates that fear of violence actually transcends spaces and is embedded in the continuous gendered experience. It translates into a fear of ‘consequences’ which can take the form of emotional or physical violence and/or judgment. From the choice of clothes to the choice of sexual partners, women’s decisions are shaped by the fear of violence either by family or by strangers. Fear coerces in the absence of violence by acting as an effective substitute.

A way forward

Fear of violence is systematically reproduced through media and crime statistics as well as cultural and social norms. It distinguishes women’s bodies as perpetually under danger and is used to monitor and influence them. It becomes a powerful tool to control female sexuality and social mobility. Even women who do not report feeling ‘fear’ talk about the ‘sensibility’ of ‘avoiding’ violence. The axiom of ‘being sensible’ makes prevention of violence a choice for women: submit or face violence. Fear, therefore, acts as a form of symbolic violence by reproducing the relations of domination and solicits quiet acquiescence from women regardless of the occurrence of violence in their lives.

It's important to think of how fear allows a smooth oscillation between ‘choice’ and ‘command’ and how one needs to shift the focus of prevention of violence away from women and towards the systems that generate it. What happens in the absence of overt violence? Are women able to make ‘choices’ freely?

Smriti R.Sharma