Part II

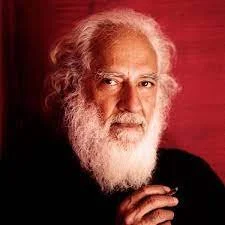

NJ. Well Arvind, since we are talking about translation, I wanted to say that as someone who grew up reading English poetry, I always knew you primarily as a poet more than a translator. Yet, the opposite seems to be true in the rest of the English-speaking world. Vidyan Ravinthran, the editor of your Selected Poems and Translations writes that ‘Mehrotra, rather like A.K Ramanujan– whose verse he has discussed brilliantly– is best known abroad as a translator’. However, the sense that I get from reading you is that you are constantly blurring the line between those two activities. Could you perhaps reflect on why that distinction is not as meaningful to you?

AKM. Songs of Kabir appeared in the US much before Selected Poems, which perhaps explains Vidyan’s comment. When you write your own poem you are not given a point from which to start and a point at which to end. You can change both at will. With a translation, you not only have to keep checking these two points but all other points in between. That said, the process of working on a translation and working on your own poem is the same. Both require you to put in the same amount of manual labour. At times you may even forget whether you’re working on your own poem or a translation. In that sense, the lines that separate them are blurry. It can also happen that while doing a translation you see, distantly, the shape of a poem that you may write in the future. Book of Rahim has translations of Rahim’s dohas followed by my own Rahim poems which would not have been written had I not read about him and his times while working on the translations. History, for me, is a way of understanding, or living in, the present. In the Collected Poems there are poems on Mahmud Ghazni, on the Ghurids, on Ghalib in old age, on a Company period drawing. Rahim lights up another area of that dark chamber called the past, which I find more engaging than the dark chamber of the present.

NJ. Is there a particular quality in the different poets that you have translated that compel you to recreate those works in your own voice?

AKM. A poet-translator can only translate in his or her voice. We, or at least I, do not have a writing voice and a translating voice. As I read a poem, and if I am thinking of translating it, I am already reading it as my poem in my voice, whose version I’ve come across in Maharashtri Prakrit, or Hindi, or Gujarati. The Absent Traveller would never have happened had Arun not read me some poems from S.A. Joglekar’s edition of the Gathasaptasati. This was in the mid-1970s, when he was living in Bhaktawar, opposite the Colaba Post Office. Joglekar’s edition runs to a thousand pages. In addition to the Prakrit text, Joglekar gives a translation in Sanskrit, followed by the Marathi. His long introduction has sections on the region’s history, its social religious, and political life, and its flora and fauna. As Arun read the gathas in Marathi and translated them for me into English, I was already hearing them as precursors to the imagist poems I was greatly influenced by. I wanted to read more gathas, to write gathas myself, but the only way I could do so was by translating them. And I did not know Prakrit or Sanskrit or Marathi. I suppose you can say that both with Kabir and the Prakrit translations, I was writing my own poems by other means.

NJ. Is there a particular quality in the different poets that you have translated that compel you to recreate those works in your own voice?

AKM. A poet-translator can only translate in his or her voice. We, or at least I, do not have a writing voice and a translating voice. As I read a poem, and if I am thinking of translating it, I am already reading it as my poem in my voice, whose version I’ve come across in Maharashtri Prakrit, or Hindi, or Gujarati. The Absent Traveller would never have happened had Arun not read me some poems from S.A. Joglekar’s edition of the Gathasaptasati. This was in the mid-1970s, when he was living in Bhaktawar, opposite the Colaba Post Office. Joglekar’s edition runs to a thousand pages. In addition to the Prakrit text, Joglekar gives a translation in Sanskrit, followed by the Marathi. His long introduction has sections on the region’s history, its social religious, and political life, and its flora and fauna. As Arun read the gathas in Marathi and translated them for me into English, I was already hearing them as precursors to the imagist poems I was greatly influenced by. I wanted to read more gathas, to write gathas myself, but the only way I could do so was by translating them. And I did not know Prakrit or Sanskrit or Marathi. I suppose you can say that both with Kabir and the Prakrit translations, I was writing my own poems by other means.

NJ. I guess you also realised that you weren’t the first person to introduce anachronisms to Kabir either. The various itinerant singers who sing Kabir’s verses regularly introduce words like ‘ticket’ and ‘station’ themselves.

AKM. I saw by and by that I was part of a long tradition. An itinerant Kabir singer in Rajasthan, as you mention, has used the words in a pada. When asked how Kabir could have known about the railway system, he replied that Kabir was all-knowing. Now if he could bring in ‘ticket’ and ‘station’, I, as a translator-singer, could bring in ‘deodorant’.

NJ. You know I also wanted to ask you this question, since if you look at Kabir, Rahim, or the poets of the Gathasaptasati, all of whom you have translated, represent such different modes of writing and poetry. How do you manage to capture such distinct voices each time you translate them?

AKM. The translator is also something of a ventriloquist. You modulate your voice to make it sound like another’s. At the same time, these different voices are not so different. Kabir is a nirgun bhakti poet. Rahim’s is largely a secular voice. But if you look at their work, as well as at the Gathasaptasati, the poems have the same feel materially—the feel of a clod of earth that you can crumble in your hand. Common to them is the simplicity of utterance, of things spoken, heard. It is there in Arun as well, in poems like ‘Three Cups of Tea’, ‘The Turnaround’, and ‘Biograph’, and in Bhijki Vahi and Chirimiri.

NJ. There’s this book on the Catus of South India–little poems in Telugu, Tamil, and Sanskrit– written by the scholars David Shulman and Velcheru Narayana Rao, called A Poem at the Right Moment. These poems are woven into the fabric of everyday life, and can be invoked by anyone who happens to remember them. Kabir and Rahim both have that quality to them.

AKM. The other thing they have in common is that they represent a collective voice, even if they go by a single name, Kabir or Rahim. In many of his poems, Kabir comes across as iconoclastic, disruptive, angry, impatient. For anyone who wished to speak out against the established order, especially caste hierarchies, he provided you with a framework. He even provided you a readymade name. All you had to do was say what you wanted to say as memorably as you could and add kahat Kabir at the end. It makes things easy.

NJ. There is another writer, this time a contemporary, that I wanted to ask you about. You have translated extensively from Vinod Kumar Shukla’s short stories and poems. For me the way you write is all about creating affinities, between different traditions, languages, eras, through the medium of literature and translation. Shukla’s work seems to resonate very deeply with you, and I was wondering if you could tell us a little bit about what makes it so compelling for you.

AKM. It is affinities more than differences that I keep noticing between writers. A few of the affinities are to be found in the epigraphs to Songs of Kabir and the notes at the back of The Absent Traveller. And I come across them all the time. Years after I had finished with the Prakrit, I spotted a Basil Bunting poem prefigured in a gatha. When I look out the literary window, I see Arun’s Jejuri and Kala Ghoda adjacent to Shukla’s Rajnandgaon and Raipur. What appears straight to us, appears askew to them. And they can both be quite funny.

NJ. The short story of his called ‘Old Veranda’, that you translated with Sara Rai is one of the strangest and most mesmerising pieces of writing that I have read. ‘College’ is another remarkable work, which I first read in the Georgia Review. I think both pieces are from Blue is like Blue. What does Mr. Shukla think about all the attention his work has been receiving recently?

AKM. Oh, Mr. Shukla, I am sure he’s happy, but he doesn’t say very much. The interviews with him that I’ve read tend to be short. You comment on his work and after listening to you he’ll agree with what you’ve said without adding anything of his own. But to return to his sense of humour. In ‘College’ he has this wonderful passage about the father’s dentures, which for his children become playthings:

‘The biggest brass lota in the house had been kept aside for Father, for his exclusive use. After meals, he would remove his dentures and put them in the water that remained in the lota. My younger brother called the dentures my father’s mouth. He would hold the dentures in his hands, open the hands in the shape of a jaw, and tell Amma to give Father a piece of the roti. The roti would drop in his palm. The dentures were made locally about a year before. Father ever afterwards complained of pain in the gums. Being a brahmin, as part of his caste duties, he was frequently invited to eat at people’s homes. Sometimes he ’d forget to wear the dentures, and Amma would nag me to go after him on my bicycle with them.’

NJ. I think that’s a delightful, and very quirky passage to conclude with. Thank you so much Arvind, for doing this.

Nachiket Joshi